|

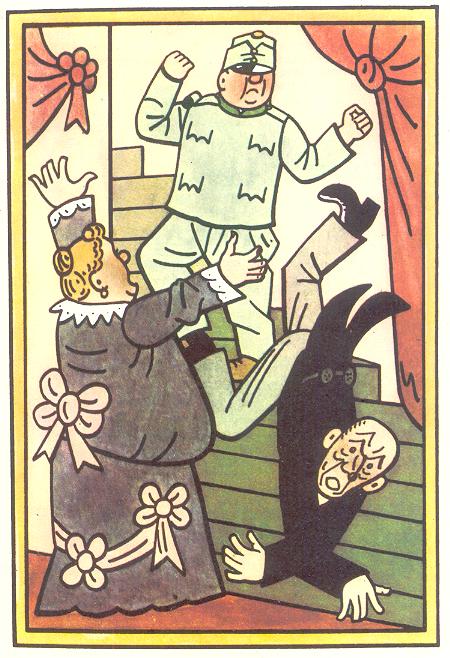

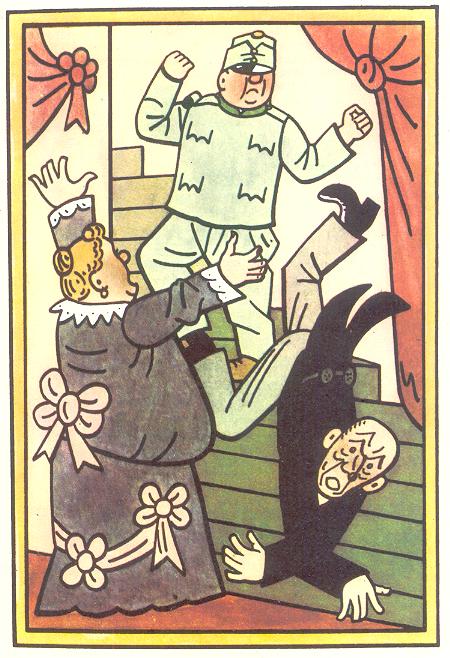

| Švejk acting forcefully in the City Café in Sanok. |

In 1915,

Švejk and his company's stay in

Sanok was brief but eventful, and as usual the Good Soldier played an important part. So did his arch enemy

Lieutenant Dub but for less heroic reasons. After arrival the latter took upon himself to inspect the town's numerous houses of ill repute and check that the men didn't slither into debauchery. In the meantime the company was ordered to march onwards towards

Sambor already the same afternoon. The

Reichsdeutsche Hannover-regiment had required the

gymnasium where the 91st regiment were supposed to be lodged and no Austrian dared stand up to their fearsome commander. By now

Dub still hadn't returned and

Švejk was entrusted with the delicate task of finding him. So he did with ease, in a secluded room upstairs in the

City Cafe; dead drunk and in the company of the alluring

Miss Ella. He was dragged out, loaded onto the sick cart, and thus started the march towards the front in a way that would not have impressed his Emperor.

In 2010, back in the editorial offices of

Pod Vihorlatom in Humenné,

Anna Šimkuličová had rung

Bogdan Strúż at Sanok Town Hall and announced my arrival in Sanok. When asked where I was going to stay I had to general amusement responded: "Where Dub stayed" (I could not remember the name of the hotel, and couldn't have pronounced it even if I had).

When I arrived in Sanok on 4 July I immediately went to the former

City Cafe. Not to look for

Lieutenant Dub or seeking and amorous encounter with

Miss Ella, but to sleep in the now very decent

Hotel Pod Trzema Różami. The staff were the friendliest I had come across in any hotel so far on the journey. The were definitely no

chambres séparées, and the WiFi connection was excellent. The hotel is located right in the centre, five minutes walk to the pretty

rynek (Market square), and even closer to the sitting statue of Švejk in the main shopping street. Down a little side street there is the pub

U Szwejka, decorated with motives from the novel. Otherwise it was an ordinary pub, the beer was disappointing and the service off-hand.

|

| Sanok rynek at night |

The next day I went to the Town Hall to see

Mr Strúż and was given a warm welcome. He took me off to a café for lunch and then picked me up after by the local

skansen. By now he had collected a ton of material for me: maps, leaflets and two books, one of them he had written the introduction to himself. It was on

Podkarpacija and I accepted it with mixed feelings: if I was given more heavy books like this I would sink when crossing the Volga.

It struck me how polite

Bogdan Strúż was. He constantly addressed me as 'pan'. Only a few days later did I discover that this doesn't only mean Sir as I had thought. It found it strange that everyone called me Sir! It is also the Polish polite form of you, similar to Czech

vy, German

Sie and French

vous. But by all means, I appreciate people who treat me politely!

I now had to start the march towards the front and set off on foot along the river

San and across the mountains towards

Tyrawa Wołoska. I soon realised that

Hašek again was way off with his timing. The company were supposed to have marched here from

Sanok in an afternoon, which is quite impossible. The route describes also seemed odd, it would have been much easier to march along the river San towards

Ustrzyki Dolne and to

Sambor from there. When I was walking up the scenic mountain road a car stopped and asked where

Sir was going. Sir's iron will-power and steely determination suddenly evaporated and he accepted the lift. It was starting to rain...

|

| Bogusław Iwanowski at work. |

In Tyrawa Wołoska I had a look around the small village. There is little more than a church, a few shops and the ruins of a stately mansion, the dwór. One of the naked columns now supports a storks nest. The history of the dwór was written on placards beneath. Tyrawa Wołoska had been attacked and burnt by UPA guerrillas as late as 1946.

A far bigger attraction was the gallery of

Bogusław Iwanowski, a unique artist of wood-carving. When I approached I noticed a number of the wooden sculptures so typical of the region and in the garden was a man busy working on a huge trunk.

Iwanowski greeted the stranger by downing the tools and showing him round the gallery and even offering Sir a glass of home-made

śliwowica. One series of sculptures depicted the life of pope John Paul II from childhood to the Vatican, another show inter-war president

Józef Piłsudski, and many more which have pure religious motives. Others are political and show scenes from the sufferings Poland had to endure during the totalitarian rule imposed by their two powerful neighbours. It is said that Poland can be compared to Jesus Christ; crucified between two bandits. This was definitely the case in 1939 but things have now fortunately changed for the better. Still these events, and many previous, have left deep traces and it is no exaggeration to say that Russians and Germans are universally disliked, often hated. The

Katyn massacre and Stalin's refusal to aid the Warsaw uprising in 1944 further added to the antagonism towards Russia. Not to mention the following 40 years of Communist rule.

Švejk's trail continued along the road to

Przemyśl and two kilometres up the scenic valley lies the village of

Berezka. Due to a series of co-incidences I ended up here on my trip in 2004. I was ill-prepared back then and arrived in

Tyrawa Wołoska without having any idea how small it was. I went to the village cafe to ask for accommodation and was told there was none, but one of the guests offered me a bed for the night. It was early afternoon but the

piwo and

wódka was already flowing, the mood was exuberant, and every other word was

kurwa.

|

| Jomar and Jurek, 2004. |

We all went up to

Berezka and after copious amounts of

wódka, gherkins and sausages everyone fell asleep. In the evening there was another visit to the cafe and more piwo. Grand-dad

Jurek told me how he in 1968, as a conscript, was forced to take part in the Warsaw-pact invasion of

Czechoslovakia. The Poles occupied the border areas and he was sent to

Ostrava. His opinion on this was crystal clear; his narrative when describing the invasion contained an unusually high count of the word

kurwa. After more vodka we both agreed that we were

dobry człowieki (good men). How that conclusion was reached none of us could remember the next day.

I woke up early and had to move on, but not without another session by a little

sklep by the road. When I reached

Przemyśl I was still semi-sozzled and immediately bought a bottle of Perrier so I could brush my teeth in the city park; using excellent French lemon-tasting mineral water. It was astoundingly refreshing after all the

wódka and

piwo.

|

| Flashback to 2004, a goat and a wonky shit-house. |

In July 2010 I knocked on the door of the same house in

Berezka. A lady opened and it was the mother of

Janus who had invited me to stay in 2004. She was washing and tidying the house as the family had recently moved to Sanok and they were trying to sell it. There was no goat in the garden anymore but the wonderfully tilting shit-house was still standing. I had used it once back then and had feared that farting too forcefully could make the whole thing collapse in a pile of floor-boards and shit.

Further up the valley I decided to call it a day, but not before having a meal at an unlikely fish bistro in the middle of the forest. It was little more than a shack but

ryba was good. I misread the bus timetables back to

Sanok, but fortunately I got a lift soon after. It was the lady who owned the fish-shop and I arrived safely back in

Sanok, and started to prepare the next leg to

Krościenko. I eastimated the distance to 25 kilometers so would be quite a long walk.

|

| Rainy Liskowate |

On 7 July the rain poured down so I dropped the walking project altogether, bought a good umbrella and caught a bus to

Liskowate, a village Hašek called

Liskowiec. This is the place where the 11th march company bought the skinniest cow in the Dual Monarchy from the Jew

Nathan, and were still skinning it many days later.

Liskowate is small and in the awful weather it was difficult to appreciate the village. I reached the wooden church through the wet grass and managed to take some pictures from under my umbrella. The

parasol also served me well on the five km walk down to

Krościenko. This place is bigger and quite drab despite the scenery. I took the bus to much more cheerful

Ustrzyki Dolne and after a few good

Leżajsk piwo at the station cafe I continued back to

Sanok. By now it had finally stopped raining.

Ustrzyki Dolne is now a tourist destination and appears quite wealthy. In 1950 it had some good luck. The Polish government "requested" a

territorial exchange with the Soviet Union, wanting to part with the coal-rich

Chervonohrad region by the river Bug and instead get a pretty but otherwise useless chunk of land around

Ustrzyki Dolne.

Stalin of course benevolently accepted, he was usually more interested in coal than in nature and prospective tourism. Of course the Polish request originated in Kremlin, just like the three Baltic states in 1940 had "applied" to become members of the Soviet Union. In retrospect it has been to

Ustrzyki Dolne's benefit: if the land swap hadn't taken place it would surely have remained a poor Ukrainian backwater.

Chervonohrad is now a post-Soviet, worn-down, heap of concrete and rust. So Stalin did Poland a favour after all…

No comments:

Post a Comment